Una chiacchierata su questo articolo:

Sofferenza e Fede: Un’antica domanda per i tempi moderni

La sofferenza è un’ombra che accompagna l’esistenza umana sin dalle sue origini. Da sempre, l’uomo si interroga sulla sua presenza, specialmente quando si scontra con l’idea di un Dio infinitamente buono e amorevole. Come può coesistere un dolore così lacerante con un amore così grande?

Questo interrogativo tormenta credenti e non credenti e spesso diventa il punto di crisi più profondo della fede. Come dice un vecchio aforisma, “È difficile concepire, nel pieno della sofferenza, di essere amati.” La sofferenza non piace a nessuno: spezza, disorienta e mette in discussione ogni certezza. Eppure, nel messaggio cristiano, essa non è un semplice ostacolo da superare, ma persino un’occasione per stabilire una relazione più profonda con Dio.

La sofferenza non è un errore

Secondo la prospettiva cristiana, la sofferenza non è un incidente di percorso o un errore di programmazione nel disegno divino. È, piuttosto, una dimensione intrinseca alla creazione stessa. Anche Cristo, incarnandosi, non si è sottratto a questa realtà, ma ha scelto di viverla fino in fondo, mostrandoci la sua inevitabilità.

Tuttavia, non tutto ha lo stesso peso. Una martellata sul dito è un dolore fisico, comprensibile e spiegabile. Ben diverso è il dolore esistenziale, quello interiore, che nasce proprio da domande che non trovano risposte immediate:

- Se Dio mi ama, perché sto soffrendo?

- Perché non interviene per fermare il mio dolore?

È in questo spazio di incertezza che nasce la crisi di fede, ma anche la possibilità di una scoperta più profonda.

Amore come relazione

Spesso, quando soffriamo, ci concentriamo esclusivamente su noi stessi e sulla nostra angoscia, ponendo a Dio una sola domanda: “Tu mi ami?”. Eppure, l’amore non è mai una strada a senso unico. Amare non è solo un atto di ricezione, ma una relazione reciproca che richiede la partecipazione di entrambe le parti.

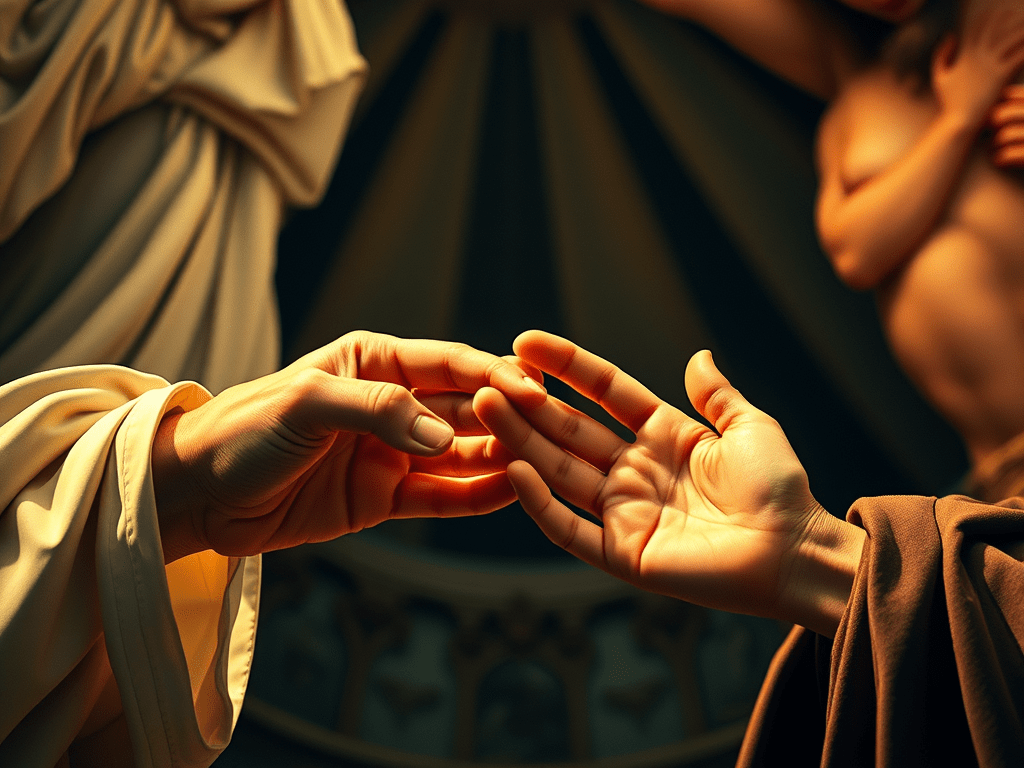

L’immagine iconica della Cappella Sistina, con le dita di Dio e dell’uomo che si protendono l’una verso l’altra, è un simbolo potente di questo incontro. Dio è proteso verso di noi, desideroso di toccarci, eppure spesso restiamo “mollemente sdraiati”, senza compiere quel piccolo gesto che completerebbe il legame. In un certo senso, la sofferenza può diventare un’occasione inaspettata per invertire la domanda, come suggerisce il testo: “È proprio grazie alla sofferenza che possiamo porci la domanda: io amo Dio?”

La gratitudine come forma d’amore

L’autore propone un parallelismo potente e illuminante: la vita stessa è il segno tangibile dell’amore di Dio. Non l’abbiamo conquistata, non l’abbiamo meritata, ci è stata semplicemente donata. Vivere, respirare, sorridere, vedere la bellezza del mondo: tutto questo è già un segno d’amore.

In assenza di gratitudine, rischiamo di non cogliere questo dono immenso. La gratitudine diventa, quindi, la prima forma concreta di amore e di risposta verso Dio. Se riconosciamo la vita come un dono, la sofferenza si ridimensiona e non neghiamo più l’amore di Dio a causa del dolore che proviamo.

Una nuova prospettiva sulla sofferenza

Sotto questa nuova luce, la sofferenza non è la negazione dell’amore divino, ma il luogo, talvolta aspro e difficile, in cui quell’amore può emergere con la sua forza più chiara. Cristo stesso, sulla croce, non ha perso la capacità di amare e perdonare, ma l’ha manifestata in modo supremo proprio nel momento del massimo dolore.

Come recita il testo originale, la prospettiva si capovolge: “Noi soffriamo, ma che fortuna che Dio ci ama, perché questo rende più lieve il nostro soffrire.” Il dolore non scompare, ma il suo peso cambia in relazione alla consapevolezza di non essere mai soli, mai abbandonati.

Conclusione

La domanda iniziale non trova una risposta semplice, ma si capovolge, trasformando un lamento in un’esclamazione di gratitudine. La sofferenza resta, ma non è più il segno dell’abbandono, bensì l’occasione per riconoscere la vita come un dono, rispondere con gratitudine e riscoprire la relazione con Dio nel modo più autentico possibile.

ENGLISH

Suffering and Faith: An Ancient Question for Modern Times

Suffering is a shadow that has accompanied human existence since its origins. Mankind has always questioned its presence, especially when it clashes with the idea of an infinitely good and loving God. How can such an excruciating pain coexist with such great love?

This question torments believers and non-believers alike and often becomes the deepest point of crisis for faith. As an old aphorism says, “It is difficult to conceive, in the midst of suffering, of being loved.” Suffering is unpleasant for everyone: it breaks, disorients, and questions every certainty. Yet, in the Christian message, it is not a simple obstacle to overcome, but rather an opportunity to establish a deeper relationship with God.

Suffering is Not a Mistake

From a Christian perspective, suffering is not a mere detour or a programming error in the divine plan. It is, rather, a dimension intrinsic to creation itself. Even Christ, in His incarnation, did not evade this reality but chose to live it to the fullest, showing us its inevitability.

However, not everything holds the same weight. A hammer blow to the finger is a physical pain, understandable and explainable. The existential, inner pain that arises precisely from questions that do not find immediate answers is quite different:

- If God loves me, why am I suffering?

- Why doesn’t He intervene to stop my pain?

It is in this space of uncertainty that a crisis of faith is born, but also the possibility of a deeper discovery.

Love as a Relationship

Often, when we suffer, we focus exclusively on ourselves and our anguish, asking God only one question: “Do you love me?” Yet, love is never a one-way street. To love is not only an act of receiving but a reciprocal relationship that requires the participation of both parties.

The iconic image from the Sistine Chapel, with the fingers of God and man reaching out to each other, is a powerful symbol of this encounter. God is reaching out to us, eager to touch us, yet we often remain “limply lying down,” without making that small gesture that would complete the connection. In a sense, suffering can become an unexpected opportunity to reverse the question, as the text suggests: “It is precisely through suffering that we can ask ourselves the question: do I love God?”

Gratitude as a Form of Love

The author proposes a powerful and illuminating parallel: life itself is the tangible sign of God’s love. We did not earn it, we did not deserve it, it was simply given to us. Living, breathing, smiling, seeing the beauty of the world: all of this is already a sign of love.

In the absence of gratitude, we risk not grasping this immense gift. Gratitude thus becomes the first concrete form of love and response to God. If we recognize life as a gift, suffering is downsized, and we no longer deny God’s love because of the pain we feel.

A New Perspective on Suffering

In this new light, suffering is not the negation of divine love, but the place—sometimes harsh and difficult—where that love can emerge with its clearest strength. Christ Himself, on the cross, did not lose the ability to love and forgive, but manifested it in a supreme way precisely at the moment of maximum pain.

As the original text states, the perspective is reversed: “We suffer, but how fortunate that God loves us, because this makes our suffering lighter.” The pain does not disappear, but its weight changes in relation to the awareness of never being alone, never abandoned.

Conclusion

The initial question does not find a simple answer, but it is turned on its head, transforming a lament into an exclamation of gratitude. Suffering remains, but it is no longer the sign of abandonment; rather, it is an opportunity to recognize life as a gift, to respond with gratitude, and to rediscover the relationship with God in the most authentic way possible.

Lascia un commento